Our heritage is threatened

Minnesota is the land of 10,000 lakes, but thousands of them are not drinkable, fishable, and swimmable. 40% of our lakes, rivers and streams are impaired, and this number is growing despite millions of dollars of investments. The groundwater that three of four Minnesotans depend on for drinking water is increasingly polluted with nitrates. Agricultural drainage projects and urban and suburban development are speeding water off the land, creating erosion and reshaping our waterways. In short, Minnesota is squandering our clean water heritage, and unless we act, we may lose it.

MCEA is taking action in the courts, at the Legislature, and in state and local governments to defend our clean water. We scrutinize pollution permits, work with local residents to identify and prevent threats to drinking water, and push for targeted investments in clean water at the Minnesota legislature. As the only conservation group regularly participating in Minnesota’s Drainage Work Group, we work with agriculture and local units of government to shape drainage policies that prevent erosion and keep water on the land. All of this work is informed by a simple principle: everybody deserves clean water.

Everybody needs water. Everybody needs clean water. It’s a right. We shouldn’t have to fight so hard for it.

Carole Thompson, Newburg Township

Limbo Creek

Learn more about MCEA’s work to protect Limbo Creek, the last free-flowing stream in Renville County, and how this will prevent erosion

What's at Stake

Minnesota stands at the headwaters of three of the largest and most important watersheds in North America - the Mississippi, the Great Lakes, and Hudson Bay. Minnesota’s water resources are globally significant, and what we do affects everybody downstream. We didn’t get into this mess overnight, and it’s going to take long-term, sustained effort to clean up and protect our water. Luckily, that’s what MCEA is built for. We work over the long haul to drive long-term systemic change that protects our water for future generations.

Our heritage at risk

40% of Minnesota waters are impaired

Hundreds of lakes and rivers are not drinkable, fishable, or swimmable

3 of 4 Minnesotans depend on groundwater to drink

Private and municipal wells provide drinking water to most Minnesotans

500,000 Minnesotans drink polluted groundwater

500,000 Minnesotans’ drinking water has nitrate pollution above safe levels

Recent Clean Water Legal Battles

Water Updates

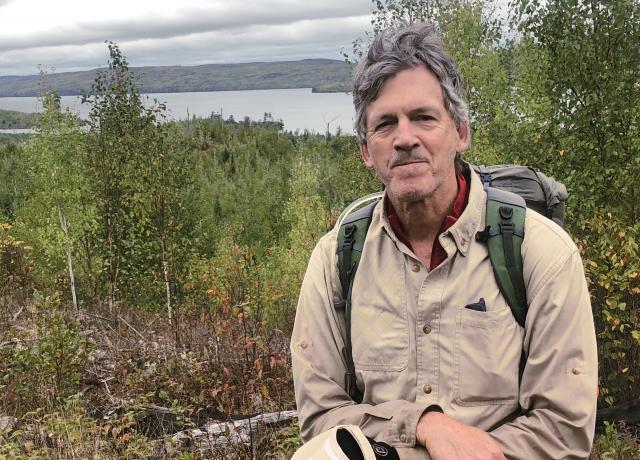

MCEA Board Member Ron Sternal on why he's a donor:

"It’s personal. I give to MCEA because I’m angry. I’m angry that the regulatory agencies that are supposed to keep my water clean, my air sweet, and my environment healthy are not doing the job. The lawyers at MCEA are my last chance to stop the polluters; hold our regulatory agencies accountable and talk sense to our elected officials. State wide, and across all environmental issues, my donations to MCEA maximize my impact, and my psychic reward that they’re not going to get away with it. I can fight back!"